ARE WE ALL CREATURES OF COMFORT? (How Nasoni's Bathroom Fountain Faucet can help those with disabilities)

Dr. G. DiLeo

December 15, 2020

Let’s face it—we consider ourselves creatures of comfort. Much of our existing technology is based on making things easier for us at the consumer level. Remote controls, automatic transmissions, programmed thermostats, and many other creature comforts sell themselves because of the easier going they create in our daily lives. Considered luxuries just a generation ago, they are now considered part of our everyday living. In his 1962 book[1], “Profiles of the Future: An Inquiry into the Limits of the Possible,” Arthur C. Clarke wrote, “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” How might one attempt explaining television to caveman? Thus, we really do live with the magic of our technology.

As creatures of comfort, however, we cannot truthfully say that all of us are able to take advantage of that ease, that magic. The easy machines, appliances, and automated processes that most take for granted fail in functionality for many persons who have disabilities. These disabilities can range from mechanical, such as loss of function of a limb; to sensory, such as deafness or blindness. Also, cognitive disabilities, such as Alzheimer disease or autism spectrum, compound the difficulty in using even everyday objects. There is also psychiatric disability which can make useless the normal functions of the body if the dissociation is severe enough.

Today’s medicine and therapeutics, however, have allowed such persons to remain active from a cognitive and motivational aspect, but that activity is still compromised when even the simplest conveniences don’t exactly work in accordance with particular physical disabilities. Frustration can result, which causes needless suffering on a psychological level, added to the already physical inconvenience. As such, a whole industry has evolved in offering assistive devices across a variety of debilities. The USA, ever sensitive to everyone “created equal,” has even enacted laws[2] to give the disabled equal access to facilities, information, and their rights as citizens.

ROME GOT IT RIGHT

While Rome never considered everyone to be created equal, this civilization went to great lengths to provide for their privileged citizens. That spirit has continued into the “all created equal” era, seen in the distribution of water, from the aqueducts to the nasones (“little fountains”). This quaint historical note leads to the interesting fact that these public water fountains in Rome inspired the Nasoni motivation to use an old trick for new purposes. The Roman outside water fountains had an ingenious capability—blocking the downward spot with a finger would force water to spring upward from a small hole on the top of the tap. This resulted in an arc of water for filling cups, for instance. This ingenuity is not surprising, considering Rome was using aqueducts to distribute water as far back as 312 BC . Nasoni used this idea and engineered its efficiency and durability into a patented, dynamic “kinetic” flow technology.

NASONI’S FOUNTAIN FAUCETS—A NEW MINDSET OF ERGONOMICS

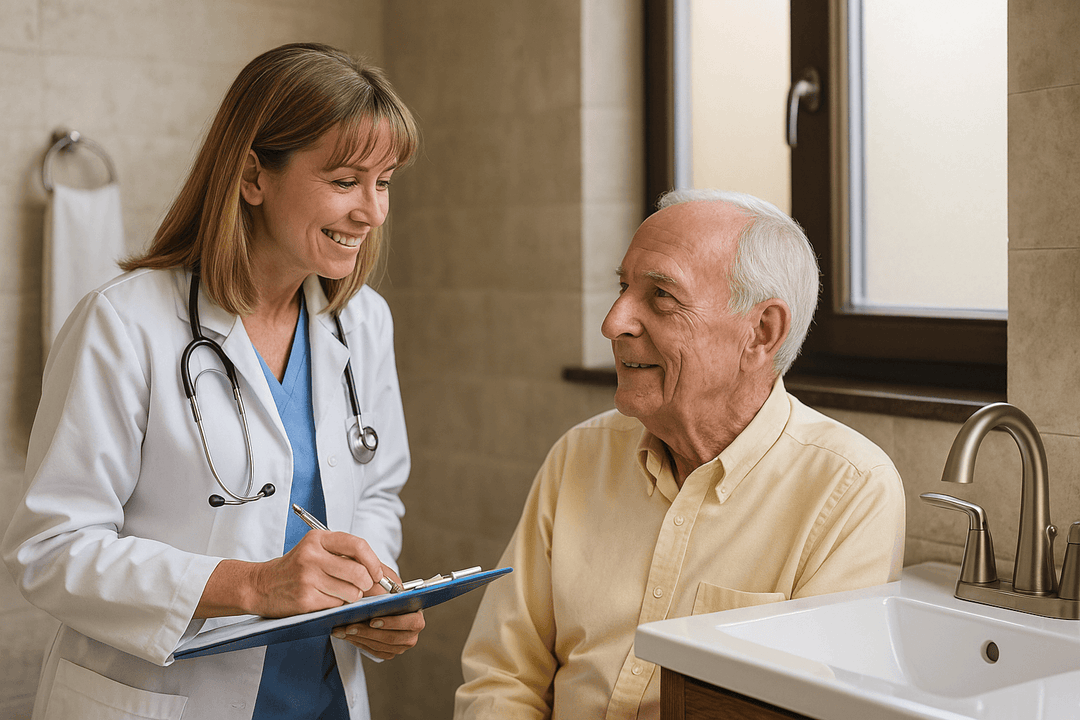

Perhaps Nasoni’s fountain faucet addresses only one aspect of the problems that disabled persons encounter, but it is a crucial one—making the simple act of using water stay simple.

As human beings, we encounter water all day long—use it, seek it out, drink it, and put it in containers for many things. We circulate it for cooling and heat. We depend on it. So, imagine depending on it but having difficulty getting it. All the time.

Conventional faucets, while having benefitted from technology, do not take into account those with disabilities; using them, while having been generally convenient in their design and function for many people, is no longer convenient for those with physical limitations. Actions that most perform intuitively include cupping of the hands to pool water for rinsing after toothbrushing, craning the neck to access the flow of water from under the faucet, rinsing after shaving, or using facial cleanser or makeup remover. For the disabled, each of these can become an ordeal, and all of these separate inconveniences accrue each day to contribute to a life of inconvenience that goes well beyond their specific handicaps. This is unfair.

Functional limitations plague the elderly, and with life expectancy climbing, the amount of dysfunction likewise will escalate. Those with pain, such as suffering rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, multiple sclerosis, fibromyalgia, neuropathic pain, and many other conditions, add to the need for ergonomics focused on them. Those with vertigo or inner ear dysfunction avoid many daily activities tied to functional positioning. Spinal disease—nerve compression, disc herniation, scoliosis or lordosis—which takes the brunt of any stooping, bending, or squatting down to sink level, is particularly problematic with the conventional design for faucets in common use today. Even cardiovascular dynamics are affected by these positioning hardships, increasing intraabdominal pressure and creating difficulty breathing with straining to assume such positions. Obesity is also no stranger to these taxing exertions, when even the simple tying of the shoes demonstrates how challenging simple tasks can become.

For Nasoni, it was clear, for physical as well as for psychological well-being, that a new mindset in ergonomics was needed for everyone to benefit from our modern technologies so that no one is left behind. This is the motif that the Nasoni fountain faucet product line champions with its award-winning proprietary, innovative, and ultimately very helpful products. Nasoni intends to extend the magic back into the lives of those so challenged. Everyone wants to be whole, and while that may be impossible, it can be mimicked successfully by the magic of technology.

The Nasoni fountain faucet products, although rendered by complex design and engineering, offer simplicity at the user end—where it is needed most. Whether it is a simple reachable lever or another way to deliver water flow, accessibility is achieved. Accessibility will make a disabled person more functional, and function is a powerful concept: it is the goal of many types of therapy and of whole specialties that deal specifically with handicaps.

THE “BETTER WAY” REPLACES “NO WAY”

A picture is worth a thousand words. All you need do is go to a demonstration video to see what Nasoni is doing for the disabled. It is changing a simple action that may be labeled “no way” for someone disabled into a better way for them. The kinetic flow technology (natural flow of energy) that drives an arc of water upward makes it accessible, for those who cannot gain access to under the conventional faucet, and effortless accessibility for their faces or mouths. This offers a godsend for them. Whether a person is born with a disability or disabilities are acquired through accident, trauma, or disease, offering water from the opposite direction can now include everyone. It also allows for elimination of unsanitary actions, such as reusing cups. When tasks become easier, they are done more frequently, portending well for dental hygiene. As medicine advances, so does the number of those in need, such as those who have undergone surgical procedures like cervical neck fusions. Chronic pain, Parkinson’s, and the many other realities which people face daily need such a re-engineered device like the Nasoni fountain faucet.

WATER IS A TERRIBLE THING TO WASTE

Using the Nasoni fountain faucet will realize an 88% increase in efficiency, reducing water use from a typical 4.4 gallons to only half a gallon over the 2 minutes typical for facial hygiene, toothbrushing, or other common sink activities. Even more when lengthier activities are engaged, such as shaving. While some may see this as yet another benefit for the handicapped—namely, lowering of the water bill—the reality is that such efficiency is good for the planet, too. “Going Nasoni” is “going green,” and at no time has this been more important than now.

THE PRODUCT, THE INNOVATION—THE NASONI DA VINCI BATHROOM FOUNTAIN FAUCET

Apple, Tesla, Google, and many others have seen the marketing value of aesthetics, from the actual product to the boxing used to encase it for transport and purchasing. Such aesthetics are particularly powerful to the human mind, setting off the right happiness neurotransmitters, such as dopamine, the reward hormone. The Nasoni Da Vinci fountain faucet follows this sensitivity in the design of its faucets. When function is also imbued with beauty, the human mind benefits on a higher level than even the way the body benefits from the increased functionality. This has inspired an artistic and appealing design, as the Nasoni faucet innovation is available in several different models. As center mounts or widespread (four-inch vs 8-inch, respectively), they come in gloss black nickel, satin nickel, and polished chrome, based on solid lead-free brass. There is also a single-level mount. They also accommodate premium under-counter water filters, available from Nasoni.

Thus, the craftsmanship of construction is superb—both sturdy and aesthetic, and so it helps both the body and the mind. Research has proven that helping both is a sum that is greater than the mere addition of its parts , so combining form and function is a win-win for the body-mind gestalt.

FIRST YOUR SINK; NEXT, THE WORLD!

Conservation of resources depends in large part on the participation of those at the consumer level. Trash recycling of paper, glass, and metals has been going on in many locations now and is even mandated in some of them. Recycling of complex substances, such as rare earths in electronics is being aggressively undertaken. That is why it is a point of great pride that many organizations have seen the sense in the Nasoni design and its ingenuity from a conservation point of view. For example, it was a consumer product finalist and honorable mention in the Fast Company 2020 World Changing Ideas competition. This is so telling, because our world is changing incredibly fast. But the changing world does not care about the finite resources it contains, so it is up to us to do this for our planet. Although water is not a “rare earth,” such as yttrium, it is indeed finite. Since its importance cannot be understated, from molecules to tissues to organs—to our entire physiologies, conserving it as the Nasoni faucet offers to do is worth the price aside from its practicality for the many people with disabilities.

CONCLUSION

Modern marketing favors the pleasingly aesthetic, creating a win-win for the body and mind interrelationship we all need for the health of both. Humanism champions functional equality for the disabled. Product stability relies on the craftsmanship involved in manufacture. All of these noble concepts are part of the Nasoni Fountain Faucet mission, to make the lives of the disabled more fulfilling by eliminating the cumbersome and tedious inequities they suffer in using everyday objects, while supplementing function with the beauty that is part of happiness.

Every now and then comes along a product that is empathetic for those in need, yet beautiful enough to stand on its own for that reason alone. When offered with the finest of craftsmanship, materials, and engineering, it is called the Nasoni Da Vinci Fountain Faucet.

[1] Clarke, A. C. (2013). Profiles of the Future. Hachette, UK. Chicago.

[2] Scotch, R. K. (2000). Models of disability and the Americans with Disabilities Act. Berkeley J. Emp. & Lab. L., 21, 213.

[3] https://www.romabbella.com/en/things-to-do-en/nasoni/

[4] http://www.romanaqueducts.info/q&a/2invention.htm

[5] Tang, Y. Y., & Bruya, B. (2017). Mechanisms of mind-body interaction and optimal performance. Frontiers in psychology, 8, 647

About G. DiLeo, MD

Dr. G. DiLeo, physician and published women's health author for McGraw-Hill, is now writing full time after a career of over 30 years in private OBGYN practice. He has served twice as Chief-of-Staff at a major regional hospital and 5 years in academics as Director of the Division of Pelvic Pain in the Dept. of OBGYN at the University of South Florida College of Medicine. He is an accomplished minimally invasive surgeon, laparoscopist, and an inventor (the catheter-stethoscope--U.S. Patent).

Leave a comment